By Refilwe Sekano

The basis of evolutionary medicine is the interplay between health, environment, and disease. Malaria and Multiple Sclerosis (MS) are examples of this interplay. Malaria is a vector-borne disease caused by the Plasmodium falciparum parasite. Malaria exerts a strong selective pressure, which results in the enrichment of alleles which may increase the susceptibility to other diseases. The Sardinian Island was plagued with malaria, and the World Health Organisation (WHO) coordinated an eradication campaign on the island in 1951. Coincidentally, after the eradication of malaria in Sardinia, there was a threefold increase in MS incidence from 1960. This was a short time for genetic changes in the Sardinian population, meaning that an environmental change was probably the likely determinant of the increased MS incidences. MS itself is a neurodegenerative autoimmune disease that attacks the CNS myelin or oligodendrocytes. Northern Europe has a high prevalence rate of MS, the Mediterranean basin has a medium and Africa has a low prevalence rate. With this, the researchers aimed to determine whether individuals with MS in Sardinia exhibited a stronger immune response to the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum compared to ethnically unrelated healthy controls and MS patients in continental Italy.

So, how did they do this?

Three experimental groups were recruited in this study. Twenty-eight patients of Sardinian ancestry with definitive MS (sMS), 28 age and sex-matched ethnic healthy controls (sHC) and 16 age and sex-matched MS patients from continental Italy were selected as controls in this study (iMS). The researchers then collected peripheral blood from the 3 experimental groups, and their mononuclear cells (MNC) were isolated by centrifugation, and then exposed to P. falciparum, and a proliferation assay was performed. Next, the researchers measured how well the MNC killed the P.falciparum parasite by determining the parasite growth by measuring the activity of its lactate dehydrogenase, measured through a 650 nm OD spectrophotometer. Lastly, the researchers conducted an ELISA test for human IL-6, TNF-𝛼 and IL-12p40 using the supernatant of the MNC proliferation test to determine how much was produced.

Their key findings.

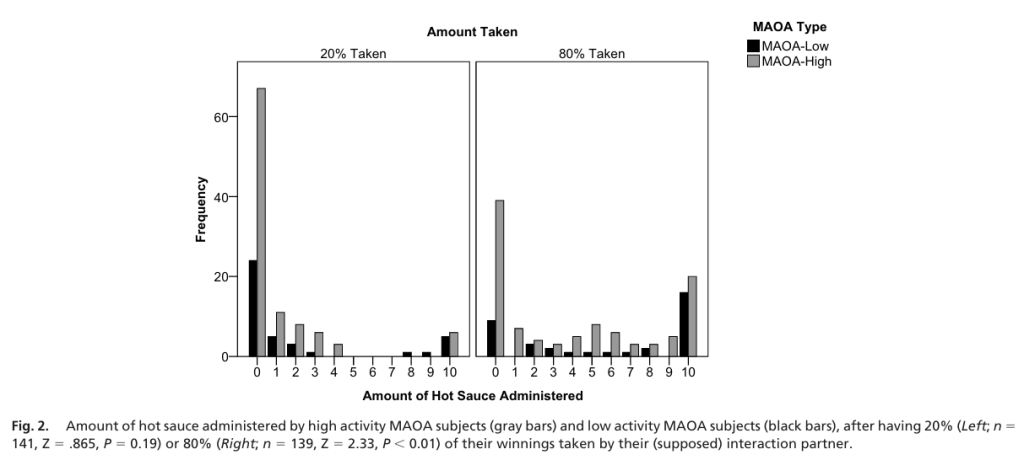

The immune response driven by P.falciparum antigens was significantly higher in the sMS patients. The killing of the malaria parasite and phagocytosis of the infected red blood cells by macrophages were significantly enhanced in the sMS patients as compared to the sHC patients. Therefore, this suggests that Sardinian individuals affected by MS have a stronger anti-P.falciparum immune response than the healthy controls and the continental Italians.

The sMS group had the highest P. falciparum-drivenTNF production, followed by the sHC and lastly the iMS group.

What can we conclude from their findings?

The Sardinian population serves as a compelling example of the complex interplay between health, evolution, and the environment. Before malaria was eradicated on the island, Sardinians survived severe forms of the disease due to their robust anti-P. falciparum immune response. However, the elimination of malaria, combined with significant improvements in hygiene, may have disrupted this positive selection pressure. This shift could have led to an overactive immune system, potentially contributing to the development of autoimmune disorders such as multiple sclerosis (MS).

Reference:

Sotigu. S., Sannella. A., Conti. B., Arru. G., Fois. M., Sanna. A., Severini. C., Morale. M., Marchetti. B., Rosati. G. 2007. Multiple Sclerosis and the Anti-Plasmodium falciparum Innate Immune Response. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 185(1-2):201–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.01.020.