by Noluntu Buyana

Have you ever wondered why some people seem naturally more are aggressive than others? Or how two people who are raised in similar environments have completely different reactions to stress or conflict? No?…..well I have so buckle up!

Violence and aggression are complex behaviours shaped by an intricate interplay of environmental, psychological and biological factors. While upbringing and social context plays a major role, researchers have increasingly turned their attention to the brain and genetics with monoamine oxidase A gene (MAOA) drawing considerable interest. The interest blossomed in 1993 when Brunner et al. reported repeated explicit aggressive and violent behaviours among males across several generations in a Dutch family. They carried X-linked missense mutation in the MAOA gene causing abnormally low MAOA enzyme activity, a condition later termed Brunner syndrome.

Loacted on the X-chromosome, the MAOA gene encodes for monoamine oxidase A enzyme, which is involved in the catabolism of neurotransmitters including dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin in the brain. These neurotransmitters are vital to mood regulation, emotional response and stress management. Two main gene variations exist: Low-activity (MAOA-L) and high activity (MAOA-H) variants. The MAOA-L results in lower levels of MAOA enzyme, leading to the build-up of neurotransmitters. It has been associated with heightened impulsivity, antisocial traits, and increased aggressive responses, particularly in males. The MAOA-H variant, by contrast, leads to faster neurotransmitter breakdown. Some studies have suggested possible links to aggression in females, though findings remain inconsistent and not solid.

The MAOA-L variant, nicknamed the “warrior gene”, has been associated with increased aggression following challenges in observational and survey-based studies, especially when combined with adverse childhood experiences. Noting the importance of childhood adversity and environmental contingences in behavioural outcomes, more studies started focusing on gene-by-environment interactions in MAOA-L individuals. McDermott et al. conducted an experiment aimed at observing how MAOA gene influence aggressive behaviour under varying levels of provocation, using the “host sauce” paradigm. They hypothesised that individuals MAOA-L will react more aggressively with high levels or provocation compared to the MAOA-H group, and not react aggressively with low provocation (i.e., gene by environment interaction).

METHODS

DNA samples were collected from 78 college male participants, and they were grouped as either MAOH-H or MAOA-L carriers. Each participant was told they were paired with an anonymous partner in a different lab (it was actually a computer). They performed a task and awarded money upon the completion. Afterwards, each participant was told their “partner” had either 0%, 20% (low take) or 80%(high take) of their earnings.

Each participant was given 10 small doses of hot sauce. To punish their partner, the participants could give their partner varying amounts spicy hot sauce knowing the other person dislikes it. Alternately, they could trade the hot sauce for money. The amount of hot sauce given was used as a measure of behavioural aggression.

KEY FINDINGS

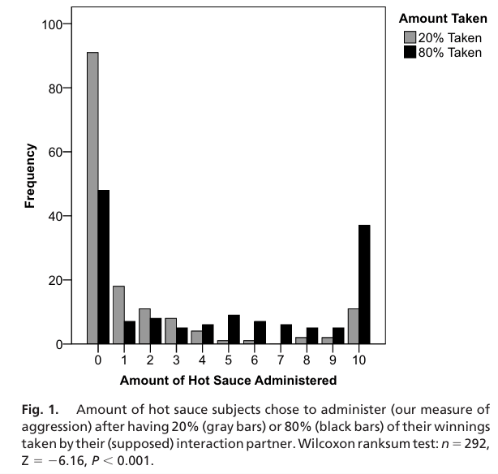

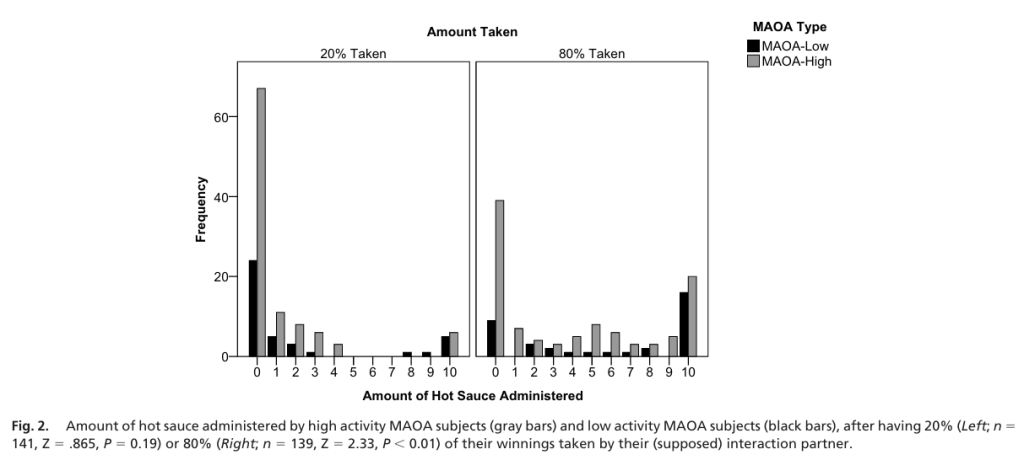

With high level provocation (i.e. when 80% was taken), participants in both groups responded more frequently and more aggressively than when 20% was taken (low provocation). Additionally, emotional survey administered after each round showed that those that lost more money reported feeling “mad” and “angry”.

Comparing different variants, they found no difference between the 2 groups when 20% was taken. They found more MAOA-L participants(75%) were significantly more aggressive than MAOA-H participants (62%) when 80% was taken. Ignoring the amount taken, MAOA-L types had higher levels of aggression overall.

Lastly, comparing proportions of observations administered the maximal amount of hot sauce punishment allowed, 44% of MAOA-L participants administered maximal hot sauce when 80% was taken compared to the 19% of MAOA-H. Additionally, 12% of participants administered maximal amount when 20% was taken compared to the 6% of MAOA-H.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

This study provided compelling evidence of gene-by-environment interaction in human behaviour. Specifically, individuals with MAOA-L variant displayed increased aggression but only when significantly provoked; that the gene does not cause aggression in isolation and context matters. This supports the idea that genetic predispositions interact with environmental triggers to cause behaviour, and MAOA gene may amplify the behavioural responses to stress or unfairness. Future work should explore the underlying psychological phenomena at work, how and why individual genetic differences cause different behavioural outcomes.

I believe referring to the MAOA-L as the “warrior gene” is an oversimplification and ignores the complexity of behaviour. It risks creating deterministic views and such labels risks dimmish personal responsibility for behaviour, especially in criminal justice context. Although some research has explored pharmaceutical interventions targeting this gene, such interventions are risky due to MAOA’s broad role in brain chemistry. Rather than reducing people to their genes, I believe more attention should be directed towards early psychological support and social interventions. Genes may load the gun, but the environment pulls the trigger…and sometimes, therapy helps keep the safety on.

References

McDermott, R., Tingley, D., Cowden, J., Frazzetto, G. and Johnson, D.D.P., 2009. Monoamine oxidase A gene (MAOA) predicts behavioral aggression following provocation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(7), pp.2118–2123. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0808376106

Mentis, A.-F.A., Dardiotis, E., Katsouni, E. & Chrousos, G.P., 2021. From warrior genes to translational solutions: novel insights into monoamine oxidases (MAOs) and aggression. Translational Psychiatry, 11(1), article 130. doi:10.1038/s41398-021-01257-2

Moon, D., 2025. MAO-A and MAO-B: Neurotransmitter levels, genetics, and warrior gene studies. GeneticLifehacks, 10 July [online]. Available at: https://www.geneticlifehacks.com/maoa/