By Alilita Lajoboda

Picture this, you are at a backyard braai. Then two of your friends show up, each carrying a different bottle of chilli sauce. One a classic store brand chilli labelled “Nicotino’s chilli sauce”, the other a homemade blend of chilli sauce made from unprocessed ingredients labelled “organic, calming CBD infusion.” One looks fiery and synthetic, the other, wholesome and handmade. Naturally, most people assume the CBD sauce is the gentler and safer option.

Here’s the twist, it’s the “natural” sauce that sets your mouth in fire, leaves your throat raw and causes a worse reaction that the store bought one ever could. That’s the paradox of vaping today, what looks like vaporized serenity, especially when it involves something like cannabidiol (CBD), known for its calming, therapeutic reputation, may be hiding more risk that we may realize. We’ve long scrutinized nicotine for its addictive nature and respiratory consequences (rightfully so), but CBD vaping has crept into popular use under a softer glow, often perceived as the natural, medicinal and safer option.

What if that perception is dangerously misleading?

Vaping is the inhalation of aerosols, commonly known as vapors, produced by an electronic device known as an e-cigarette or vape pen. Over the past decade, vaping has gained popularity, first as a “safer” alternative to cigarette smoking and then as a trendy vehicle for cannabis consumption. However, research warns us that, just because it’s a vape pen, that does not necessarily mean it’s benign. In this study, researchers from Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, set out to answer a vital question: Are the lungs affected differently when people vape CBD compared to nicotine?

Methods

To answer this question, the researchers then conducted an in vivo inhalation study in mice and in vitro cytotoxicity experiments with human cells to assess the pulmonary damage-inducing effects of CBD or nicotine aerosols emitted from vaping devices.

Pulmonary inflammation in mice was evaluated using histological analysis, flow cytometry, and quantification of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Lung injury was assessed through histology, measurement of myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, and levels of neutrophil elastase in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and lung tissue. To evaluate lung epithelial and endothelial barrier integrity, BAL protein concentrations, albumin leakage, and pulmonary FITC-dextran permeability were

measured. Oxidative stress was assessed by determining the antioxidant capacity in both BAL fluid and lung tissue. The cytotoxic effects of CBD and nicotine aerosols on human neutrophils and human small airway epithelial cells were examined using an in vitro air–liquid interface (ALI) exposure system.

Key Findings

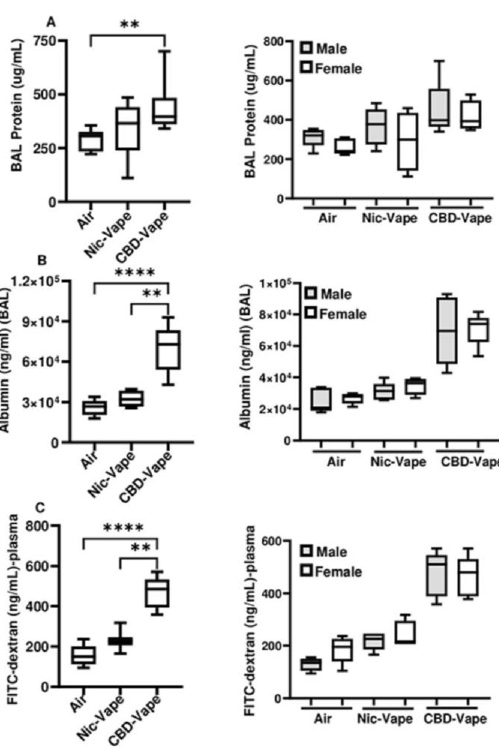

Figure 1: Markers of lung damage induced after inhalation exposure to CBD and nicotine aerosols.

Exposure to CBD aerosols resulted in more lung endothelial damage than exposure to niciotine aerosols. This was because total protein levels in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) were elevated following inhalation of CBD aerosols compared to air-exposed controls (Fig 1A). Furthermore, serum albumin leakage into the BAL was significantly increased after CBD aerosol exposure relative to both nicotine aerosol and air exposures (Fig 1B). In addition, systemic leakage of FITC-dextran from the lungs into the plasma was substantially higher following CBD aerosol inhalation compared to nicotine aerosol exposure (Fig 1C). There were no statistically significant differences observed in the levels of these markers when comparing male with female mice.

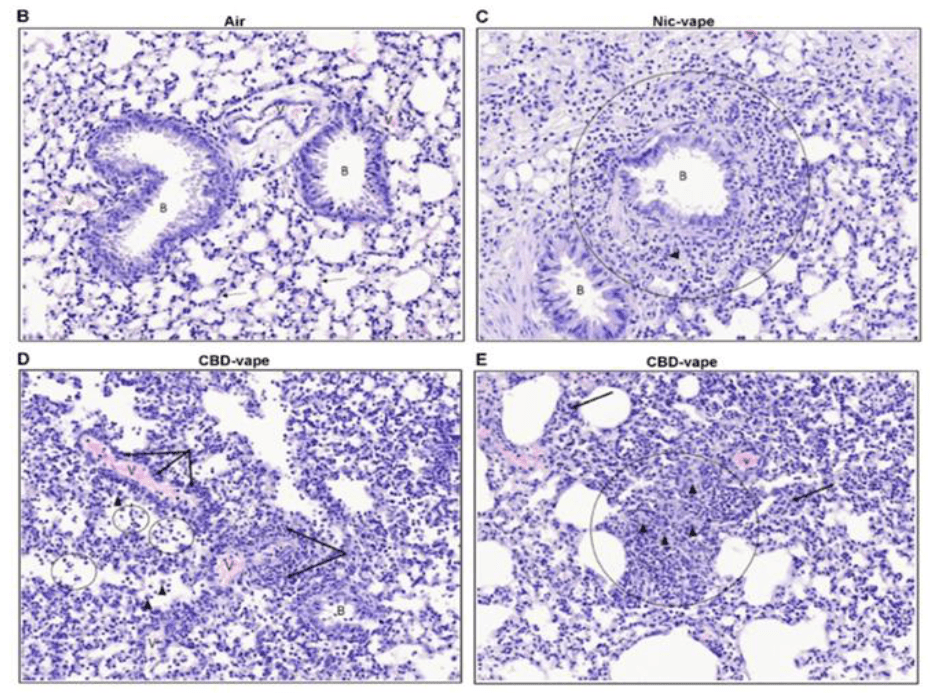

Figure 2: Inflammatory changes in the lungs following inhalation exposure to CBD and nicotine aerosols.

Exposure to CBD aerosols resulted in greater accumulation of innate and adaptive immune cells in lungs compared with nicotine exposure. This is because histological analysis of H&E-stained lung tissue sections from control mice exposed to filtered air revealed normal lung architecture, with air-filled alveolar spaces bordered by thin alveolar walls (Figure 2B). In contrast, peribronchiolar and/or intrabronchiolar, perivascular, alveolar infiltrates and interstitial infiltrates of lymphocytes, macrophages and granulocytes were the predominant finding in the CBD and nicotine exposed mouse lungs (figure 2C–E). Both small focal lesions and larger, more regionally extensive lesions were observed, predominantly near terminal bronchioles and frequently in subpleural regions. The incidence and severity of these lesions were notably higher in mice exposed to CBD aerosols compared to those exposed to nicotine aerosols.

Conclusion and take aways.

This study highlighted that the use vape pens for the purpose of inhaling CBD containing aerosols causes significant severe damage to the lungs and more significant inflammatory responses on the lungs compared to the inhalation of nicotine. However, this does not mean that the vaping of nicotine is safe. In my opinion, no form of vaping is without harm and avoiding all vaping is the healthiest cost. After all a braai with no chilli sauce, is still a great braai.

Reference

Bhat TA, Kalathil SG, Goniewicz ML, Hutson A, Thanavala Y. Not all vaping is the same: differential pulmonary effects of vaping cannabidiol versus nicotine n.d. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2022-218743

Leave a comment