by Tony Noveld

In this study, researchers from the University of Cape Town, the Ragon Institute, and the Francis Crick Institute set out to answer a vital question: Why does Mycobacterium tuberculosis remain the world’s deadliest bacterial pathogen despite decades of research and treatment efforts? This 2025 review synthesizes over three decades of molecular, cellular, animal, and clinical studies to build a comprehensive understanding of how the tuberculosis bacterium evades and manipulates the human host to survive and spread.

How Did the Researchers Approach This?

Rather than generating new experimental data, the authors performed a narrative synthesis. They systematically reviewed hundreds of peer-reviewed articles spanning microbiology, immunology, pathology, and epidemiology. This integrative approach allowed them to connect diverse findings from genetic profiling studies, experimental infection models in mice and non-human primates, detailed analyses of human tissue samples, and comprehensive TB epidemiological data. The review bridges laboratory discoveries with clinical observations to clarify how bacterial biology translates into disease dynamics in real-world human populations.

Key Findings: A Master of Cellular Sabotage

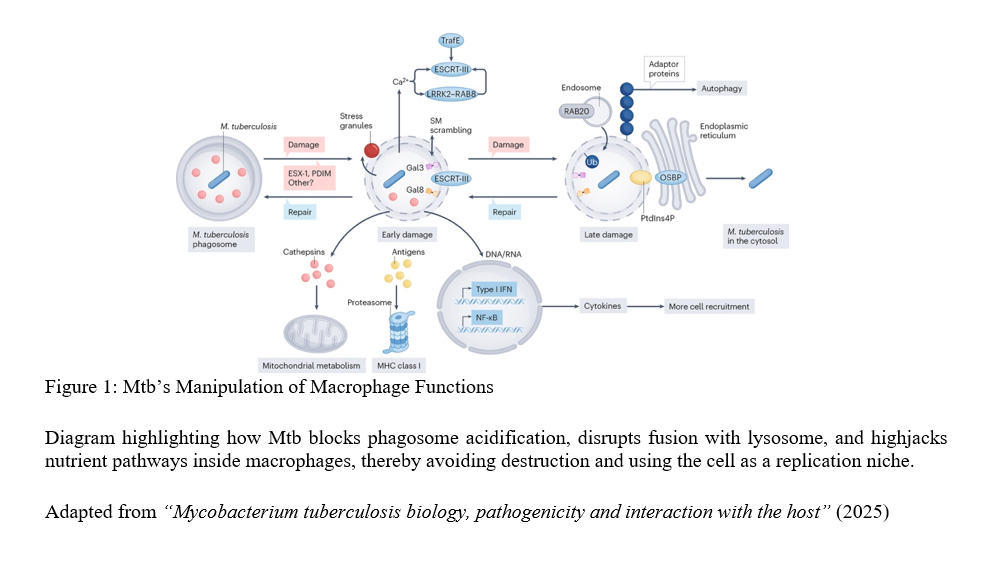

The review reveals that the tuberculosis bacterium is not a passive survivor—it actively reprograms the very immune cells meant to destroy it. When inhaled, tuberculosis bacteria are engulfed by macrophages, immune cells designed to digest pathogens inside acidic compartments called phagosomes. However, the bacterium employs sophisticated countermeasures: it blocks phagosomal acidification and disrupts phagosome-lysosome fusion, effectively stalling its own degradation The bacterium also hijacks host nutrient pathways, redirecting cellular resources for its survival. Remarkably, some tuberculosis bacteria can escape into the cytosol—the cell’s interior—gaining additional freedom to manipulate host processes.

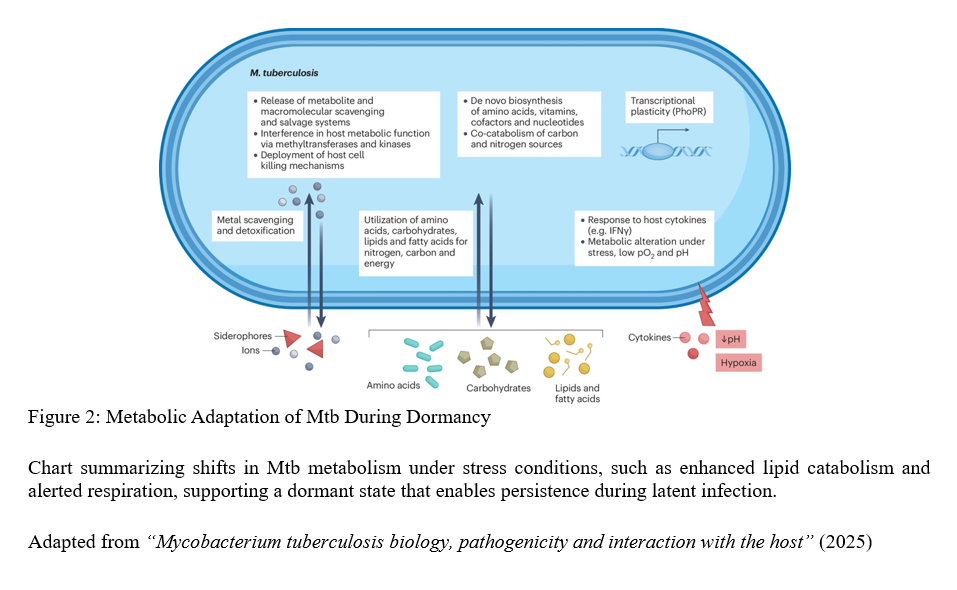

The tuberculosis bacterium demonstrates metabolic flexibility rarely observed in other bacteria. It can shift between multiple energy sources and slow its growth to enter dormancy states lasting years. This remarkable adaptability underpins latent TB infection, where individuals carry live bacteria without symptoms, creating a hidden reservoir for future disease and transmission.

The Granuloma: Fortress or Safe Haven?

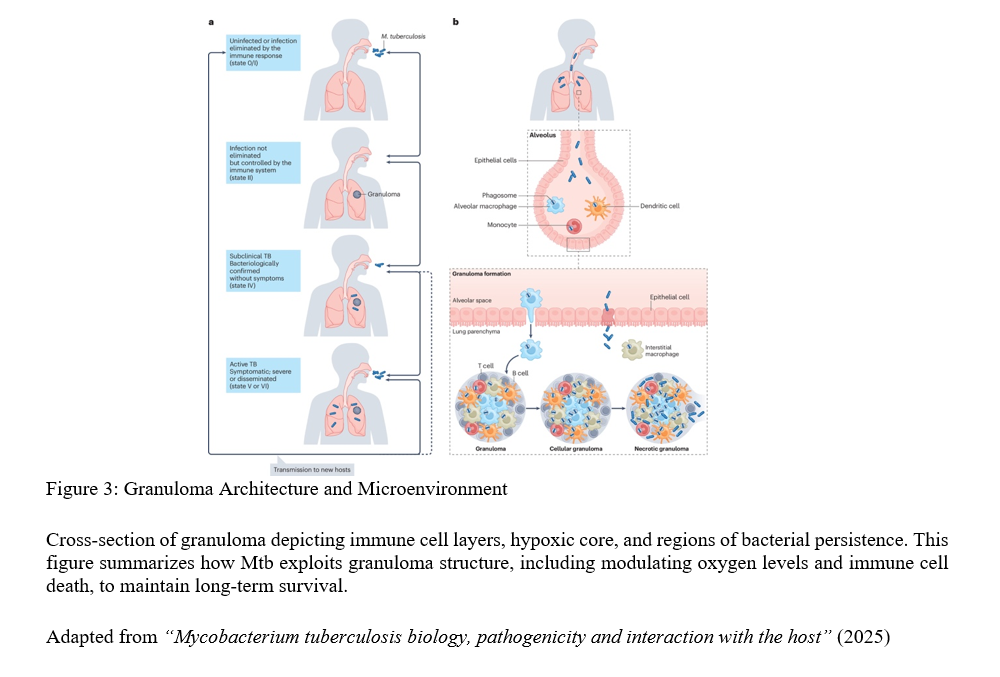

The battle primarily occurs within granulomas—organized clusters of immune cells designed to contain the tuberculosis bacterium. Rather than static fortresses, granulomas represent complex, dynamic ecosystems where the bacterium manipulates oxygen levels and programs immune cell death pathways to create favourable microenvironments. This constant interplay between bacterial survival strategies and host containment attempts explains why granulomas sometimes fail, resulting in active disease and destructive tissue damage.

A Silent Epidemic: Asymptomatic TB and Transmission

Perhaps most concerning is the “silent reservoir” of asymptomatic infections (see figure 3) highlighted by the review. Large-scale prevalence surveys reveal approximately half of TB-positive individuals lack classical symptoms like persistent cough or fever. Despite appearing healthy, many remain capable of transmission, severely complicating global identification and treatment efforts.

Strengths and Limitations

The narrative synthesis effectively bridges research silos, connecting molecular insights with clinical and epidemiological realities. However, limitations exist: much mechanistic data derives from animal models that don’t perfectly mirror human TB (at no fault of the authors), human tissue studies face accessibility constraints, and critical gaps remain regarding reactivation triggers—being key unknowns for prevention strategies.

Personal Interpretation and Implications

This synthesis reaffirms the tuberculosis bacterium’s extraordinary adaptability, evolved through millennia of human co-evolution into a master of immune evasion rather than aggressive virulence. The bacterium’s ability to manipulate macrophages, survive within granulomas, remain dormant for years, and persist asymptomatically explains TB’s resistance to eradication despite available drugs and vaccines.

As someone studying infectious diseases, and an upcoming clinician-scientist, this review fundamentally reshapes my understanding of TB latency. It’s not a binary state but a nuanced spectrum involving complex host-pathogen dialogues. It highlights a critical public health challenge: focusing solely on symptomatic cases misses much of the infectious reservoir. Future interventions must integrate improved diagnostics for silent infections, host-directed therapies targeting immune manipulation, and social interventions addressing environmental factors.

The review underscores that TB research cannot occur in isolation. Breaking the transmission cycle demands integrating laboratory discoveries with clinical observations and epidemiological data—a true “bench to bedside to community” approach that may finally outsmart the bacterium’s sophisticated defences.

Conclusion: An Ongoing Arms Race

Nearly 150 years after TB’s discovery, Mycobacterium tuberculosis remains humanity’s most formidable bacterial adversary not through aggressive virulence, but via intricate, highly evolved immune system interactions. This 2025 review emphasizes that defeating TB requires understanding this complex biological dance in all its dimensions. Only with such comprehensive insight can we develop the innovative diagnostics, treatments, and preventive measures needed to finally tip the scales in humanity’s favour.

Blog based on: “Mycobacterium tuberculosis biology, pathogenicity and interaction with the host,” 2025 review.

References

Warner, D.F., Barczak, A.K., Gutierrez, M.G. et al. (2025). Mycobacterium tuberculosis biology, pathogenicity and interaction with the host. Nature Reviews Microbiology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-025-01201-x

Leave a comment