by Zifikile Mose

Ever found yourself thinking, “What am I doing here?” or “Do I really belong here?” That creeping doubt that you are somehow not good enough despite evidence to the contrary is more common than you think. It is called the impostor phenomenon, and yes, most of us go through it.

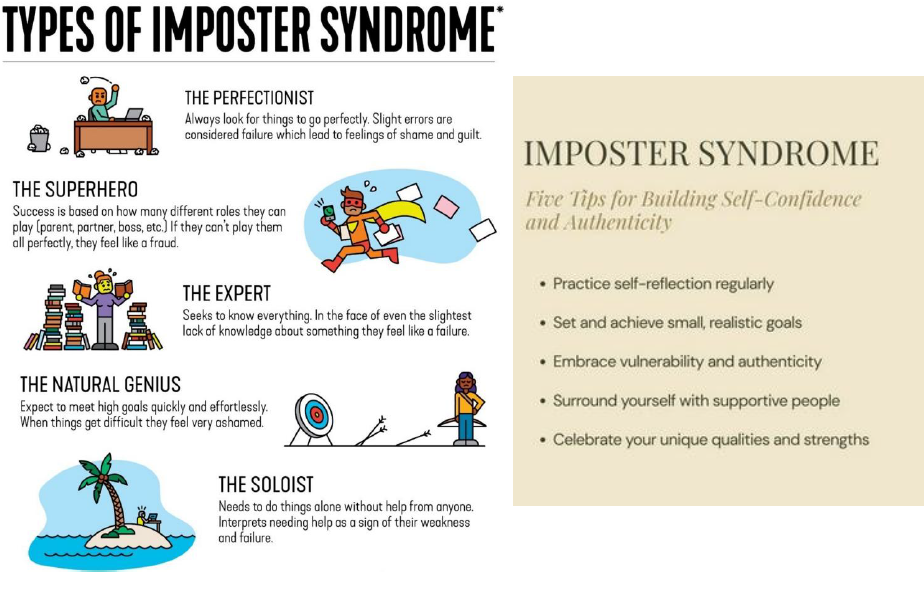

Imposter phenomenon, commonly known as “imposter syndrome,” is defined as feeling like a fraud, where competent and successful individuals doubt their achievements. They believe they are less capable or less deserving of their roles or accomplishments. This phenomenon is often linked to thoughts such as, “What am I doing here?” “I am not good enough,” or “I feel like a fraud.” Instead of trusting their abilities and strengths, most people experiencing the impostor phenomenon attribute their successes to luck, deception, others’ kindness, or external factors unrelated to their competence. This phenomenon was first studied among successful, predominantly white female professionals in the United States by Clance and Imes (1978). While the term “impostor syndrome” is more commonly used, “impostor phenomenon” more accurately describes the experience of feeling like a fraud, as “impostor syndrome” could be mistaken for a stigmatizing mental health condition requiring medical treatment.

Impostor phenomenon does not discriminate; everyone at some point in their academic career suffers from it, from students to researchers or even scientists at the top of their academic careers. This phenomenon can impede the development of a sense of belonging in the field or domain, contributing to eventual departure from the academy.

While previous research has centred on students in higher education, faculty experiences of the impostor phenomenon remain underexplored. This gap was addressed by Chakraverty (2020), whose study looked at academic events or activities that could contribute to faculty experiences of the impostor phenomenon. Using a qualitative analysis of fifty-six interviews, this U.S.-based study examined the occurrence of and experiences among faculty who self-identified as experiencing the impostor phenomenon. A prior survey of the same participants revealed that they were predominantly White and female, experiencing moderate, high, or intense impostor phenomenon.

The study highlighted several recurring themes tied to impostor phenomenon experiences in both research and teaching. These included peer comparison, faculty evaluation, public recognition, the anticipatory fear of not knowing, and perceived lack of knowledge. The study showed that antecedents of the impostor phenomenon could be similar for academics (e.g., PhD students, postdoctorates and faculty), some of these common antecedents include, fear of public recognition (e.g., receiving awards), comparing oneself unfavourably with one’s peers, fear of public speaking or scientific writing, hesitation to apply knowledge, and feeling undeserving of and unqualified for a role.

Impostor phenomenon is prevalent in hypercompetitive academic environments with a culture of “publish or perish,” making those from marginalised groups, such as women and racial and/ or ethnic minorities, question their place in the profession. External environments also contribute to the impostor phenomenon; for example, negative academic environments, including sexual and non-sexual harassment, can make women experience the impostor phenomenon within their field.

Coping with the impostor phenomenon begins with shifting our mindsets, how we think about ourselves, and our progress in academia. Comparison is the thief of joy; instead of viewing your colleagues as competitors, see them as opportunities to learn from. Whether we like it or not, failure is part of the learning process. We need to embrace it as a learning opportunity, a chance to reflect on what went wrong and identify potential solutions.

One of the most important things is to ask for support or help; most faculty members or other students will have experienced the impostor phenomenon at some point in their careers and can offer first-hand advice on how they coped with it. Finally, the author suggested that a deeper examination of how the impostor phenomenon manifests within faculty will not only help in designing tailored mentorship and professional development for faculty members but also benefit PhD students and postdoctoral researchers who will join the faculty workforce in the future.

References

Abdelaal, G. 2020. Coping with imposter syndrome in academia and research. The Biochemist, 42(3), pp.62-64.

Chakraverty, D. 2022. Faculty experiences of the impostor phenomenon in STEM fields. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 21(4), pp.84.

Leave a comment