By Rofhiwa Musoliwa

While Zika, dengue, and West Nile steal the spotlight, another mosquito-borne virus has quietly crossed borders: Sindbis virus (SINV). Recently detected for the first time in southern Spain during routine surveillance, SINV’s surprise arrival points to a silent spread from Africa. Once limited to northern outbreaks, its unexpected presence in Europe signals a need to rethink our viral watchlist.

Background

Sindbis virus, a member of the Alphavirus-genus (Togaviridae family), is closely related to Chikungunya virus. It was first isolated in Egypt in 1952 and has since been associated with sporadic outbreaks in Northern Europe and Russia. It is transmitted by mosquitoes (mainly Culex species) and amplified in birds. Humans, although not part of the main transmission cycle, can become accidental hosts, often developing fever, rash, and joint pain, sometimes lasting for years. However, humans are considered dead-end hosts, meaning the virus does not circulate further from person to person.

How was SINV discovered in Spain?

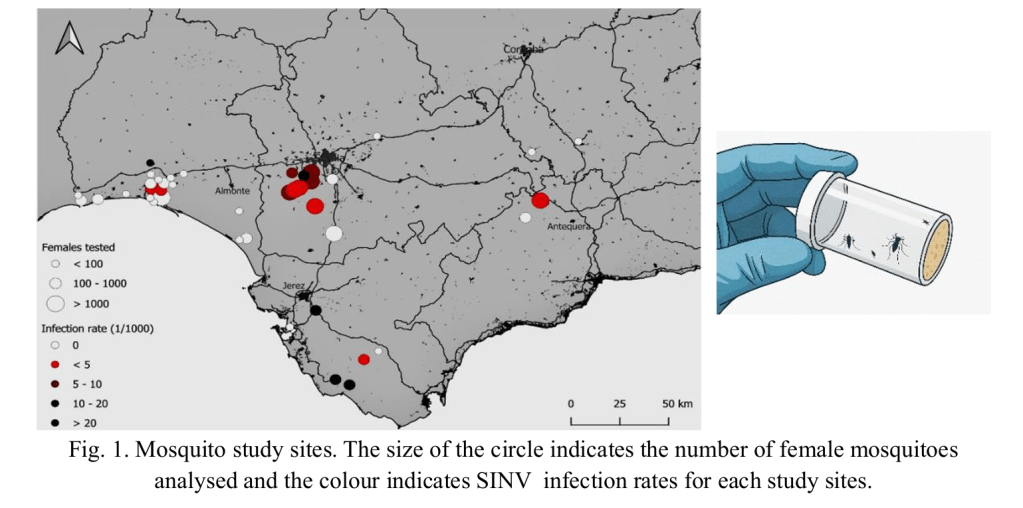

As part of the West Nile virus surveillance, researchers screened mosquito pools using real-time RT-qPCR followed by sequencing. Out of 31,920 mosquitoes trapped across 42 sites, 1,149 pools were tested. SINV RNA was detected in 137 pools, representing a striking 11.92% positivity rate, with Culex perexiguus mosquitoes showing the highest infection rate.

The team did not stop at detection, and they cultured viruses, sequenced 16 full SINV genomes, and performed phylogenetic analysis to understand where these viruses came from.

Genetic clues point to Africa

All 16 Spanish SINV genomes belonged to Genotype I; the same genotype associated with human outbreaks in Europe and Africa. However, these isolates formed a distinct clade, closely related to strains from Algeria and Kenya, not Finland or Sweden. Using Bayesian evolutionary analysis, the study estimates that this virus likely arrived around 2017, probably via migratory birds.

Implications

The detection of SINV in Spanish mosquitoes raises important public health considerations. If the virus is actively circulating among birds and mosquitoes, and if bridge vectors like Culex perexiguus, which feed on both birds and humans, are involved, then spillover to humans is plausible.

Future Studies

Culex perexiguus is a likely vector, but laboratory studies are needed to confirm its ability to transmit SINV. Human surveillance and serological testing in high-risk areas may uncover undiagnosed infections. Integrated vector management, including reducing mosquito populations and improving public awareness, can limit the risk of spillover. Coordinated One Health surveillance monitoring of mosquitoes, birds, and humans is essential.

References

Gutiérrez-López, R., Ruiz-López, M. J., Ledesma, J., Magallanes, S., Nieto, C., Ruiz,S., … & Vázquez, A. (2025). First isolation of the Sindbis virus in mosquitoes from southwestern Spain reveals a new recent introduction from Africa. One Health, 20,100947.

Lundström, J. O., & Pfeffer, M. (2010). Phylogeographic structure and evolutionary history of Sindbis virus. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 10(9), 889-907

Leave a comment