By Naadiya Seedat

What if we could listen or look our way towards better mental health? That’s the promise behind a fascinating new approach to treating psychological disorders – one that uses music, light, and brain-computer interfaces to nudge the brain into healthier rhythms.

It sounds like science fiction, but it’s rooted in real neuroscience. And in a country like South Africa, where access to mental health care is severely limited, this could represent an incredible opportunity.

South Africa is in the grip of a silent epidemic. Depression and anxiety affect more than 1 in 4 adults, yet fewer than 25% of those affected receive treatment within a year. The costs are staggering – an estimated R218 billion in productivity is lost per annum due to depression alone.

Why aren’t people getting help? Many feel uncomfortable with psychotherapy or fear the side effects of psychiatric medication. That’s where non-invasive brain stimulation comes in: offering a treatment that doesn’t require speaking, swallowing pills, or even leaving one’s home.

The symphony occurring upstairs

Your brain is constantly humming with electrical activity. These rhythms, or brain waves, shift depending on your mental state:

| Wave Type | Frequency (Hz) | Function |

| Delta | 0.5–4 | Deep sleep |

| Theta | 4–8 | Meditation, drowsiness |

| Alpha | 8–13 | Relaxed alertness |

| Beta | 13–30 | Focused thinking |

| Gamma | >30 | High-level cognition |

By exposing the brain to external stimuli – like sound or light – at specific frequencies, it can begin to synchronize or entrain to those rhythms. This phenomenon, called neurological entrainment, means we can potentially guide the brain into more desirable states. For example, slow-tempo ambient music might increase alpha and theta waves, promoting relaxation or creativity. Fast-paced music may enhance beta activity and sharpen focus

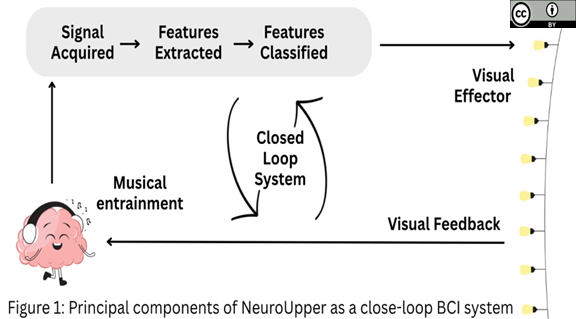

A brain-computer interface (BCI) is a device that reads your brain activity and interacts with it in real time. One prototype, NeuroUpper, uses a closed-loop system: it reads brain waves via EEG, then responds with synchronized light flickers and music to help shift those waves toward a healthier state. This is visualized in Figure 1.

Making it happen

In a recent pilot study, participants with high levels of anxiety and depression received five weekly sessions for 11 weeks. What was the goal? To reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms through audio-visual entrainment.

Who Was Involved?

Participants were:

- Aged between 18 and 60

- Had a depression score of 8 or higher on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D)

- Scored in the top 5% for trait anxiety on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

- Provided informed consent to take part in the trial

They excluded anyone with:

- Dementia (MMSE score <23), major health issues, or a history of alcohol abuse

- Photosensitive epilepsy

- Current suicide risk or enrolment in other clinical studies

Study Design

Researchers recruited 45 adults with high levels of depression and anxiety. Participants were split into two groups:

- The control group attended informal support sessions and watched non-interactive mental health videos.

- The experimental group received NeuroUpper neurostimulation – five sessions a week for 11 weeks. They wore headsets that delivered music and flickering light, adjusted in real time to their brain activity.

Here’s the twist: the system used a passive brain-computer interface, meaning it read spontaneous brain activity in real time, then altered the music and light patterns to guide the brain toward a more desirable mental state. The user didn’t need to “do” anything — just relaxed and let the system respond to their internal rhythms.

This created a closed-loop feedback system, where the music influenced brain activity, which then influenced the next round of stimulation, like a musical conversation between the brain and machine.

Rewiring Rewards

The results were promising:

- Participants receiving NeuroUpper showed a decrease in depressive symptoms, linked to changes in beta wave activity – the band associated with thinking and emotional regulation.

- Alpha wave changes (especially Alpha-2) predicted reductions in state anxiety, aligning with its role in calming neural processes.

- Theta activity correlated with improved performance IQ, suggesting entrainment may also benefit cognitive function.

And perhaps most significantly, participants reported feeling more relaxed, focused, and emotionally well.

Despite the encouraging results, this is early-stage science. The study was limited by its small sample size, lack of follow-up EEGs, and the prototype nature of the NeuroUpper system. Moreover, results across similar studies are inconsistent, possibly due to variation in EEG measurement methods and entrainment protocols.

And then there’s the elephant in the room: can this be done in South Africa at this scale?

Probably not (yet).

BCIs are costly, require specialized training, and raise serious ethical concerns about data privacy. Most South African healthcare settings lack the infrastructure to implement these systems equitably. Still, this technology could complement traditional therapy in well-resourced settings or pave the way for future low-cost tools.

Beyond depression and anxiety, brain-computer interfaces have been explored for:

- Assisting stroke patients with communication

- Rehabilitation and assistive technology for those with mobility impairments

- Managing ADHD, OCD, and PTSD

- Even entertainment and gaming (think thought-controlled video games)

The idea is simple: if you can understand the brain’s language, you can begin to talk back.

Conclusion: Music, Mood and the Mind

The fusion of neuroscience, sound, and technology is unlocking incredible possibilities. While we’re not at the point of prescribing Mozart over meds, we are starting to understand how sensory experiences shape the brain in real time, and how we can harness that to help people heal.

It’s not a cure at all. It’s not magic. But it is a new note in the ever-evolving symphony of mental health care.

References

Craig A, Mapanga W, Mtintsilana A, Dlamini S, Norris S. Exploring the national prevalence of mental health risk, multimorbidity and the associations thereof: a repeated cross-sectional panel study. Front Public Health. 2023 Oct 18;11:1217699. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1217699. PMID: 37920573; PMCID: PMC10619674.

Cuadros DF, Tomita A, Vandormael A, Slotow R, Burns JK, Tanser F. Spatial structure of depression in South Africa: A longitudinal panel survey of a nationally representative sample of households. Sci Rep. 2019 Jan 30;9(1):979. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37791-1. PMID: 30700798; PMCID: PMC6354020.

Ingendoh RM, Posny ES, Heine A. Binaural beats to entrain the brain? A systematic review of the effects of binaural beat stimulation on brain oscillatory activity, and the implications for psychological research and intervention. PLoS One. 2023 May 19;18(5):e0286023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0286023. PMID: 37205669; PMCID: PMC10198548.

Maiseli, B., Abdalla, A.T., Massawe, L.V. et al. Brain–computer interface: trend, challenges, and threats. Brain Inf. 10, 20 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40708-023-00199-3

Principal components of NeuroUpper as a close-loop BCI system © 2025 by Naadiya Seedat is licensed under CC BY 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Tomlinson M, Grimsrud AT, Stein DJ, Williams DR, Myer L. The epidemiology of major depression in South Africa: results from the South African stress and health study. S Afr Med J. 2009 May;99(5 Pt 2):367-73. PMID: 19588800; PMCID: PMC3195337.

Zhang H, Jiao L, Yang S, Li H, Jiang X, Feng J, Zou S, Xu Q, Gu J, Wang X, Wei B. Brain-computer interfaces: the innovative key to unlocking neurological conditions. Int J Surg. 2024 Sep 1;110(9):5745-5762. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000002022. PMID: 39166947; PMCID: PMC11392146.

Leave a comment