By Wilson Mupfururirwa

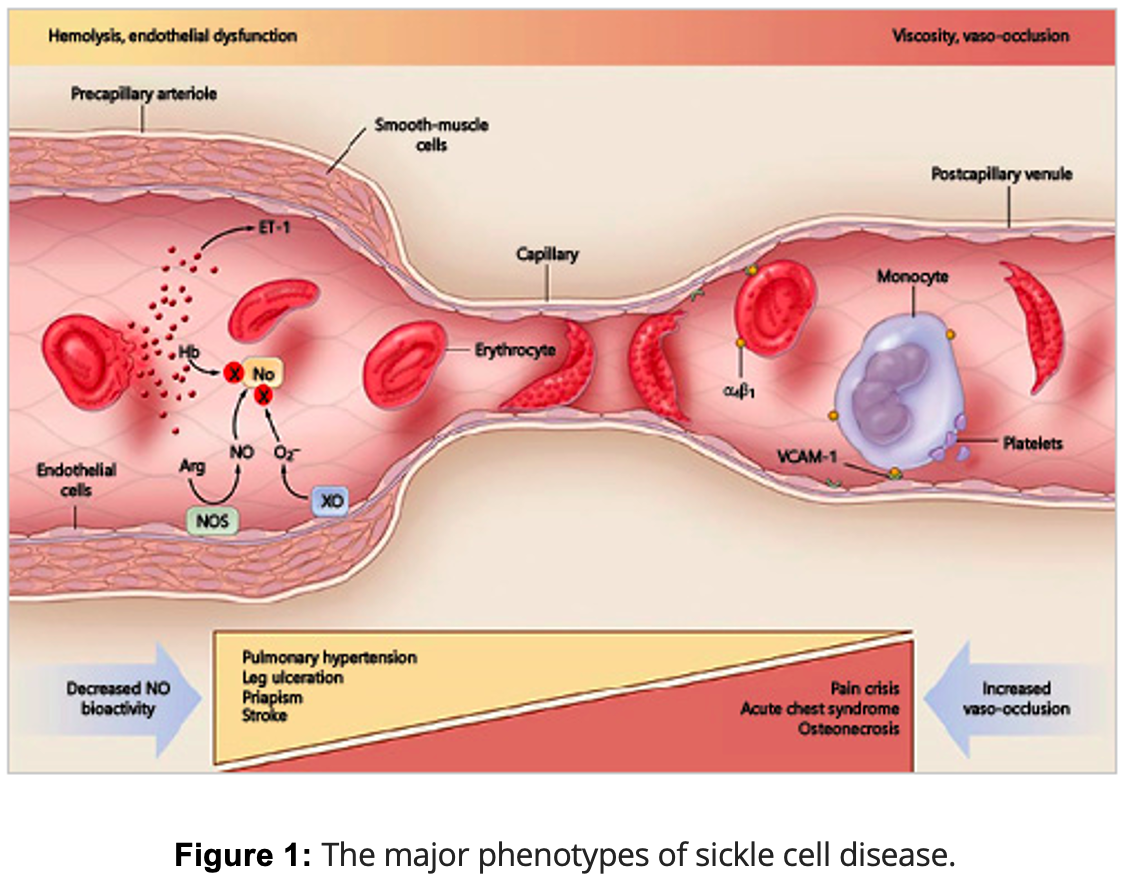

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is a genetic disorder where abnormal hemoglobin (HbS) causes red blood cells to become rigid and sickle-shaped, disrupting normal blood flow. This mutation replaces glutamic acid with valine in the hemoglobin protein, causing red blood cells to clump together when oxygen levels are low. As a result, these sickled cells block small blood vessels, leading to severe pain, organ damage, and a higher risk of infections. Two primary complications of SCD are hemolysis—where red blood cells break down too quickly, leading to problems like stroke and pulmonary hypertension—and vaso-occlusion, which results in painful crises and acute chest syndrome. SCD can affect any organ, with the spleen being particularly vulnerable early in life, increasing infection risk, while older patients may face chronic kidney and lung issues.

Fetal hemoglobin (HbF) plays a crucial protective role in SCD. This protection is evident as affected infants usually remain symptom-free until HbF levels naturally drop after about six months of age. HbF prevents red blood cells from sickling by making hemoglobin more soluble and less prone to clumping. High HbF levels are linked to milder SCD, fewer complications, and reduced disease severity. The regulation of HbF is governed by genetic factors, including β-globin gene cluster haplotypes like Arab-India and Senegal, and key genetic modifiers such as BCL11A and HMIP. These genetic variations play a significant role in determining HbF levels and influence how severely SCD manifests in individuals. However, even with high HbF, patients can still experience a wide range of symptoms.

Mutations in genes like BCL11A and HMIP, which regulate HbF production, have a major impact on HbF levels and its protective effect against sickling. HbF distribution can be varied, with some red blood cells containing high levels while others have very little, reducing overall effectiveness. Trans-acting loci, like BCL11A and MYB, also influence HbF levels. BCL11A acts as a repressor of HbF production, and variations in this gene can alter disease severity. Similarly, SNPs in the HBS1L-MYB intergenic region affect HbF levels by regulating genes involved in red blood cell development.

This genetic diversity leads to varied responses to treatments like hydroxyurea (HU), particularly in populations like those in Sub-Saharan Africa, where genetic and environmental factors play a crucial role. Research continues to identify genes that drive this variability, with certain haplotypes such as the Senegal and Arab-Indian haplotypes being associated with higher HbF levels and milder disease compared to the more severe Central African Republic (Bantu) haplotype. HbF levels vary significantly across populations and geographic regions, with the Arab-India haplotype showing the highest levels (~30%) and African haplotypes ranging from 4-12%.

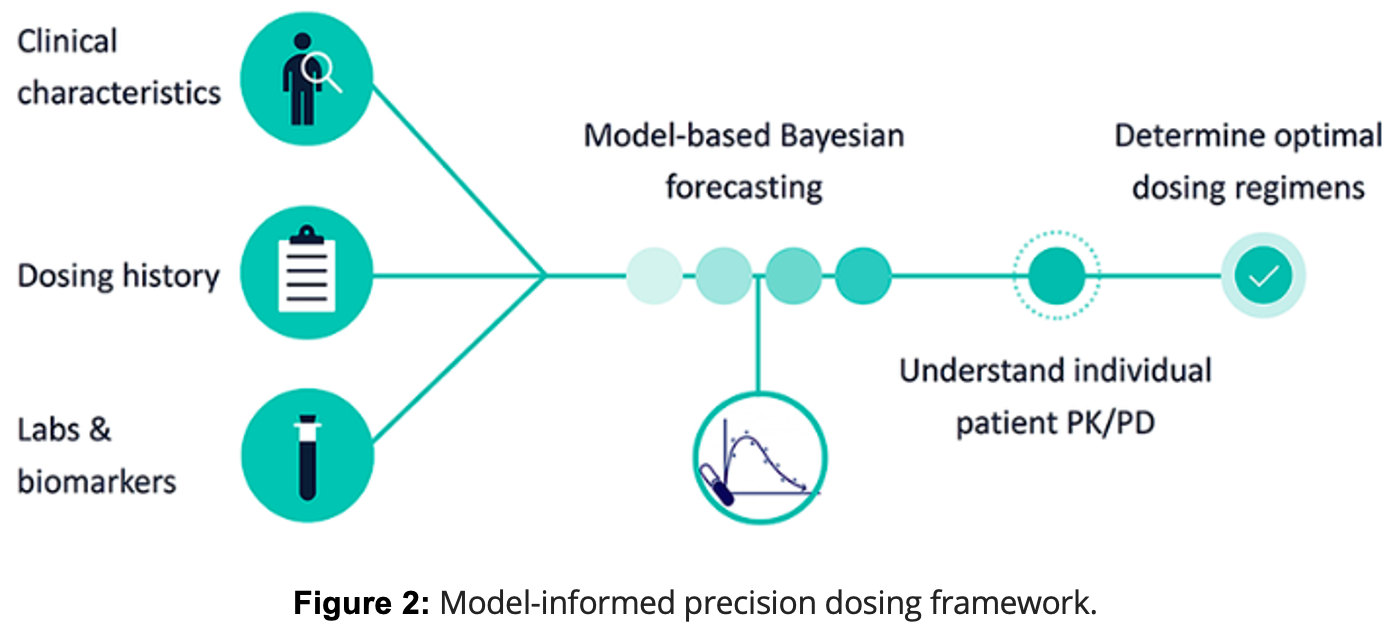

Given the significant genetic and phenotypic variability in Sickle Cell Disease (SCD), treatment strategies are increasingly moving toward personalized approaches that account for individual genetic differences. One of the most promising of these is precision dosing, particularly of hydroxyurea (HU). Precision dosing is a treatment approach that tailors drug dosing to the individual based on their genetic, clinical, and pharmacokinetic data, rather than using a one-size-fits-all model. In the context of HU, precision dosing involves adjusting the dosage based on how each patient metabolizes the drug, which is influenced by their genetic makeup. Researchers have demonstrated the effectiveness of precision dosing in clinical settings. For instance, studies like the TREAT trial found that pharmacokinetic-guided dosing led to significantly higher HbF levels—often exceeding 30–40%—compared to standard weight-based dosing methods. This approach resulted in faster attainment of optimal dosing and better clinical outcomes, including a reduction in pain crises and hospitalizations. The personalized adjustments also minimized side effects by ensuring that each patient received the most effective dose for their unique genetic profile. By using models such as pharmacokinetic-guided dosing, healthcare providers can determine the optimal dose of HU that maximizes HbF production while minimizing adverse effects, leading to a more effective and individualized treatment for SCD patients.

In regions like Sub-Saharan Africa, where SCD is highly prevalent and genetic diversity is considerable, individualized HU dosing models hold great potential. The genetic variability among SCD patients in these areas often influences how well they respond to standard treatments. Precision dosing models, such as those used in clinical trials like the TREAT study, have shown that adjusting HU doses based on genetic and pharmacokinetic data can lead to faster attainment of optimal dosing and better clinical responses. This approach is particularly valuable in settings where access to frequent laboratory monitoring is limited, making it challenging to implement traditional dosing methods. By integrating knowledge of genetic modifiers, such as BCL11A and HMIP, and leveraging precision medicine techniques, healthcare providers can develop more effective, tailored therapeutic strategies. This ongoing research supports the potential for personalized treatment plans that not only improve clinical outcomes but also enhance the quality of life for SCD patients globally, particularly in resource-limited settings where standard care approaches are limited.

Dong M, McGann PT. Changing the Clinical Paradigm of Hydroxyurea Treatment for Sickle Cell Anemia Through Precision Medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Jan;109(1):73-81. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2028. Epub 2020 Oct 8. PMID: 32869281; PMCID: PMC7902468.

Steinberg MH. Fetal hemoglobin in sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2020 Nov 19;136(21):2392-2400. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007645. PMID: 32808012; PMCID: PMC7685210.

Leave a comment