By Yeuko Manganyi

Ophidiophobia is the term used to refer to the irrational fear of snakes but for many people this fear is well founded. Every year up to 5.4 million people suffer from snakebites, of these more than 2.7 million result in envenomings (being exposed to venom). 400 000 of these people will have some sort of permanent disability with a further 138,000 losing their lives due to the venom and associated complications.

Antivenom is the most effective tool we have to combat envenomings. Antivenom is produced by stimulating the production of antibodies in a host, this is done by injecting small amounts of the venom into the host for a prolonged period then extracting these antibodies from the blood of the host once they’ve reached peak concentration. This solution is time consuming and incredibly expensive, with the resulting antibodies needing to be kept in cold storage after extraction and purification.

Most envenomings happen in remote, rural regions of sub-Saharan Africa and South-east Asia, with many of the victims being children and agricultural workers. Antivenom costs anywhere from $50−350 per dose, with some patients needing treatments that requiring up to 20 doses to be effective.

The cost of producing the antivenom, the specific storage requirements and the difficulty of getting it to areas where people need it most are only a handful of limitations introduced by antivenom as we know it today.

Researchers at the Amsterdam Institute of Molecular and Life Sciences developed a method of analyzing venoms that may revolutionize antivenoms as we know them, through what they termed “High Throughput Venomics”.

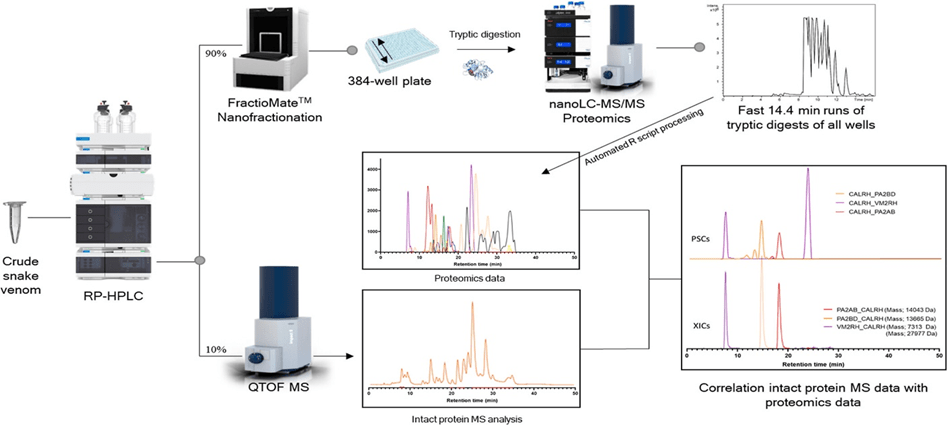

For their investigation the researchers acquired venoms from 20 different venomous snake and put these venoms through a full proteomic analysis. To do this the researchers implemented a combination of RP-HPLC, nano-fractionation analytics, mass spectrometry analysis and automated in-solution tryptic digestion along with venom database data to not only analyze but also fully categorize the components that make up each venom. This method allowed the researchers to identify each protein and peptide that makes up each venom while only taking 3 days!

The major issues with current antivenoms available in the tropical world include their limited para-specific efficacy, poor dose efficacy (10−20% of the generated antibodies are specific toward venom toxins), and a high chance of inducing severe side effects (reported in up to 75% incidences). Better knowledge about each component that makes up venom and its method of action can better equip us to develop precise compounds that counteract them, compounds that work for more than just one kind of snakebite and compounds that are viable even in tropical settings. High Throughput Venomics removes the time and animal resource restrictions imposed by the more traditional method of antivenom production, this can allow us to manufacture antivenoms that are more effective and more broadly applicable with fewer off target effects.

Compounds in venoms from sea snails have been shown to be effective pain killers, without the addictive properties of opioids. It is as yet unknown what we may find in snake venoms that may have properties that are potentially therapeutic in various unexplored ways. This is the hope for High Throughput Venomics, not only does it make the development of antivenoms a faster more straight forward endeavor, but it also may be a new avenue for treatment options for a myriad of conditions.

Resources

- High-Throughput Venomics. Julien Slagboom, Rico J. E. Derks, Raya Sadighi, Govert W. Somsen, Chris Ulens, Nicholas R. Casewell, and Jeroen Kool Journal of Proteome Research 2023 22 (6), 1734-1746 DOI: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.2c00780

- Ortiz-Prado, Esteban, et al. “Snake antivenom production in Ecuador: Poor implementation, and an unplanned cessation leads to a call for a renaissance.” Toxicon 202 (2021): 90-97.

Leave a comment