By Jamie Langson

We’ve all experienced the sense of frustration that arises when we possess knowledge but lack the means to act upon it, haven’t we? For well over a century, scientists have been aware that roughly 90% of cancers have extra chromosomes, but couldn’t exactly determine what this aneuploidy did due to the lack of means for manipulation. This puzzling phenomenon was, in a sense, the unaddressed elephant in the oncology room. However, this changed recently when a team of researchers from Yale University School of Medicine discovered that the intuition of scientists from way back then, was indeed correct. The study, published in the journal Science, aimed to determine whether aneuploidy in cancer cells are drivers of the disease and whether it represents a form of “aneuploidy addiction.”

Various computational and functional techniques were employed to facilitate the analysis of aneuploidy in cancer. Among these techniques, the use of CRISPR stood out. The research team introduced a new approach to this gene-editing technique, enabling the removal of entire chromosomes from cancer genomes, a feat previously considered unattainable. They applied this method to melanoma, ovarian and gastric cancer cell lines. This groundbreaking technique is known as ReDACT, which stands for Restoring Disomy in Aneuploid cells using CRISPR Targeting. They utilized ReDACT-NS (negative selection), ReDACT-TR (telomere replacement) and ReDACT–CO (CRISPR only) to generate a panel of isogenic cells devoid of common aneuploidies, allowing for a detailed study of its effect.

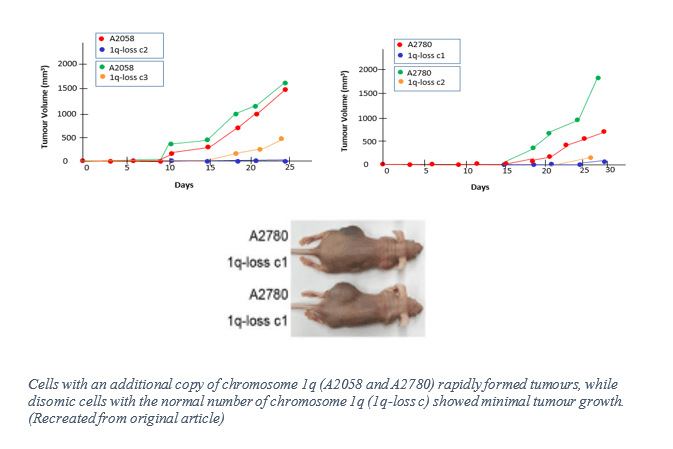

Essentially, they successfully removed the third copy of the chromosome 1q, a genetic anomaly frequently observed in numerous cancers, known to be linked to disease progression, and repeatedly occurs early in cancer development. Upon removal, tumours from this subpopulation of cancer cells were unable to grow in both petri dishes and in live mice.

Another significant finding was that when MDM4 expression was increased by the additional third copy of chromosome 1q, p53 signalling was suppressed, consequently promoting tumour growth. Together, this was conclusive evidence that extra chromosomes within cancer cells are in fact, drivers of the disease. Furthermore, the study demonstrated that cancer becomes more sensitive to drugs due to aneuploidy in its genomes. The researchers therefore speculated that this “aneuploidy addiction,” similar to “oncogene addiction,” where the loss or inhibition of a single oncogene triggers cancer regression, may provide therapeutic vulnerabilities for cancer. For now, CRISPR is merely a tool, not a therapy, but the advances made by this team of researchers may point towards a new approach of targeting cancer in the future.

Reference

Girish, V., Lakhani, A.A., Thompson, S.L., Scaduto, C.M., Brown, L.M., Hagenson, R.A., Sausville, E.L., Mendelson, B.E., Kandikuppa, P.K., Lukow, D.A., Yuan, M.L., Stevens, E.C., Lee, S.N., Schukken, K.M., Akalu, S.M., Vasudevan, A., Zou, C., Salovska,B., Li, W., Smith, J.C., Taylor, A.M., Martienssen, R.A., Liu, Y., Sun, R., Sheltzer, J.M. (2023) Oncogene-like addiction to aneuploidy in human cancers. Science 381, 1-14. DOI: 10.1126/science.adg4521

Leave a comment