by Rachel Brown

Macy is a 6-year-old girl with microcephaly, a neurological condition resulting in a reduced brain size. Due to her condition, Macy has experienced developmental delays, problems with her balance and coordination, as well as always being the shortest in her class. Since she was diagnosed, Macy’s parents have been asking many questions about her condition, including how it develops and if there are any new advances in microcephaly research that can give them any more information. One of the major limitations in the study of neurological disorders, such as microcephaly, is the lack of a suitable experimental model. Recently, cerebral organoids have emerged as a model for studying neurodevelopment and neurological disorders. These cerebral organoids are created from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which can generate any cell type in the human body and are differentiated into small aggregates of neural progenitor cells.

Macy’s parents are well read in the field and were very excited when they came across a paper titled “Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly” from the Lancaster Laboratory 1 . In this paper, the researchers established a protocol for creating cerebral organoids and have shown how they are able to recapitulate the gene expression of an in vivo brain and they use this to model microcephaly.

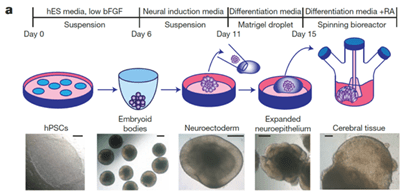

The cerebral organoids were generated by providing the iPSCs with very specific culture conditions to direct them to form cerebral tissue (Figure 1). They characterized the cerebral tissue using a variety of different experiments, such as looking at the gene expression of forebrain and hindbrain markers and staining to visualize the localization of these markers. They also stained for specific cell populations, such as neurons and radial glial cells as well as more mature neurons later in the culture period. This confirmed the presence of specific forebrain and hindbrain regions as well as cortical layers in the cerebral tissue. The researchers, however, do make it clear that there is need for further development of the protocol to ensure all brain layers are represented.

Figure 1: Description of cerebral organoid culture system (adapted from figure 1 of the paper)

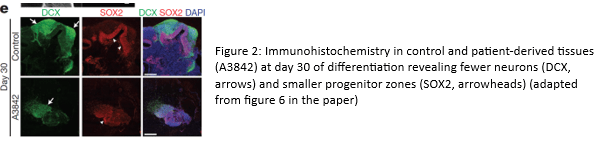

Next, the researchers used iPSCs, from an individual with a mutation that causes microcephaly, to produce cerebral organoids to model this disorder. As expected, the microencephaly organoids were smaller than controls and the protocol was adjusted to allow them to grow to the same size as controls for easier comparison. Similar experiments were conducted as mentioned above, followed by rescue experiments that involved fixing the mutation to produce normal sized organoids. This confirmed that the microencephaly phenotype was due to the loss of the protein coded for by the mutated gene, leading to premature neural differentiation and a loss of neural progenitors and, thus, a smaller brain size.

This paper is one of the first to show the use of cerebral organoids in modeling brain development and neurological disorders. Research like this gives insight into the pathogenesis of conditions such as microcephaly. It is studies like these that can help answer questions like those of Macy’s parents. They also provide comfort in knowing that we are one step closer to understanding brain development and what happens when this goes wrong!

References 1 Lancaster, M. A. et al. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 501, 373-379 (2013). https://doi.org:10.1038/nature12517

Leave a comment